Originally Published at Project-Syndicate.org, October 25, 2019

NEW YORK – The United States today does not look much like former President Ronald Reagan’s description of a “shining city upon a hill.” Strategic thinking, moral clarity, accountability, integrity, and courage seem foreign concepts to President Donald Trump and many other current US leaders. So, it is a good time to reflect on the example of Americans who have actually lived up to the county’s ideals.

Consider a father-son duo who reshaped America’s military. Their story begins during World War II, in the Solomon Islands. Victor, a young Marine Corps officer, is wounded and bleeding through his uniform; he is aided by Jack, an equally young Navy officer who administers first aid. A grateful Victor promises that if he survives, he will bring Jack a good bottle of whiskey.

Years later, Victor Krulak has become a Marine Corps general, renowned for being instrumental in the creation of the Higgins boat – which helped turn the tide of WWII for the Allies in Europe – and for introducing the helicopter to modern warfare. He walks into the White House and shares a bottle of Three Feathers whiskey with Jack – that is, President John F. Kennedy. Kennedy intends to make Krulak a four-star general and Commandant of the Marine Corps, and Krulak’s wife is encouraged to buy an additional set of stars in preparation. But first, Kennedy must go to Dallas for a campaign stop. He never returns.

Following Kennedy’s assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson notoriously sidelines his predecessor’s advisers. When Krulak confronts Johnson about America’s deeply flawed Vietnam strategy, his fate is sealed. Krulak never receives that fourth star and eventually retires.

Victor H. Krulak, November 30, 1943

LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON

Meanwhile, his son, Charles “Chuck” Krulak, twice wounded in Vietnam, rises through the Marine Corps ranks. In 1995, President Bill Clinton invites Chuck, along with his wife and elderly parents, to the Oval Office, where he makes him a four-star general and names him Commandant of the Marine Corps and a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. To mark the occasion, Clinton pins that now-rusty fourth star, bought decades earlier for his father, on Chuck’s shoulder.

This story alone is remarkable for its historical sweep. But even more important is what the younger Krulak went on to do with his new position. On day one, he issued to 200,000-plus Marines a strategic plan detailing what he intended to accomplish during his term, as well as a “values” card bearing three words: honor, courage, and commitment. Under “courage” were the words: “Do the right thing, in the right way, for the right reasons.” Every Marine was required to sign the card, and would be held accountable to its message.

Krulak invited all Marines to share their thoughts about improving the Corps. He gave out his email address, and demanded that everyone take ownership of their collective endeavors. He received tens of thousands of ideas, and considered every single one of them.

Krulak went on to fundamentally reshape the US military, introducing a concept that has since been adopted by countries as varied as the United Kingdom, Israel, and Singapore. Recognizing that modern warfare might require military action, peacekeeping operations, and humanitarian aid within the space of just three city blocks, he advocated training under all three conditions simultaneously. In a “Three Block War,” even soldiers at the lowest level would need high-level leadership skills, so Krulak created the role of “strategic corporals” – junior unit leaders who could function at a level well above their rank and make major decisions if needed.

But remember, this was the 1990s. With military service having declined in popularity among young career seekers, the Army and Navy had lowered their admission standards to attract recruits. Krulak, however, took the opposite approach. He believed that what young people really wanted was not an easy route, but a harder one: to be tested, pushed, and forced to reach for a better version of themselves. Accordingly, he raised admission standards, lengthened basic training, and launched a sweeping recruitment campaign around the opportunity to be one of “The Few, the Proud, the Marines.” Soon enough, Marine Corps recruitment growth outpaced that of all the other military branches.

Krulak then created “The Crucible,” a 54-hour epic culmination to basic training involving no sleep, more than 45 miles of marching, and a barrage of challenges that would force recruits to work together to survive. This became a new rite of passage. The recruits would finish at sunrise in front of a life-size replica of the Iwo Jima Memorial. Under a flying American flag, Krulak or his deputy would personally pin the Eagle and Globe on each young man or woman’s shoulders, officially recognizing them as US Marines. And almost always, each new Marine would weep, ready to do whatever it took to protect their country.

Charles “Chuck” Krulak (pictured second from right), September 23, 1996

SWEATING THE DETAILS

Leadership takes place at 30,000 feet, where abstract concepts are turned into strategies. But it also unfolds just inches off the ground. In what Krulak called “kicking boxes,” he would spend one week out of every month at US bases, showing up unannounced, and ask unsuspecting Marines what needed to be improved. One day, a young Marine in Okinawa stuttered his response: he loved the Corps, but his boots were not waterproof, and his feet were often wet.

Back at the Pentagon, where a four-star Marine commandant is treated like the Pope, Krulak delved into the mundane business of boot procurement. He went all the way to Congress to get Gore-Tex gear for tens of thousands of Marines stationed around the world. Everyone knew their leader cared about the small stuff as much as the big stuff.

Sometimes, leadership requires self-sacrifice. In 1999, following Clinton’s impeachment, the White House tried to change the military code of justice to water down the punishment for commanding officers who engage in inappropriate relations with their subordinates. But Krulak made it known that he would not allow the Marine Corps motto to be changed to “Semper Fidelis, usually.” He prepared to resign in protest, and the White House backed down.

After retiring from the military, Krulak continued to serve his country. When he became president of Birmingham-Southern College, the institution was struggling. Today, it is thriving, and hosts a leadership institute named in his honor. Now in his late 70s, when most former military leaders would have long since left public service, Krulak is busier than ever, fighting human trafficking and working to bridge the Israeli-Palestinian divide.

Chuck Krulak may not be a well-known name today, but he is one of numerous Americans to whom the US owes a great deal. Notwithstanding many of the country’s current leaders, there are still men and women with a moral compass as clear as the North Star – bright enough for others to navigate by. They remind us that vision without true strategic thinking is hollow, and that leadership without integrity isn’t leadership at all.

CLEAN LEADERSHIP

Likewise, consider two other men who have fundamentally reshaped modern society for the better. As with the Krulaks, few today may know of William (Bill) Ruckelshaus (pictured top) and Gerald (Jerry) Grinstein, two close friends who now live near Seattle, on the shores of Lake Washington. But through the lives of these men, both now in their 80s, we can glimpse the promise that American leadership once held – and what it might yet hold again.

Between them, Ruckelshaus and Grinstein laid the foundation for the environmental-protection, public-health, and consumer-protection laws that citizens throughout the developed world now take for granted. They each held top positions in government and the corporate sector, and one of them (Ruckelshaus) played a pivotal role in holding President Richard Nixon accountable for his misdeeds in office. Through it all, both conducted themselves with selflessness, optimism, equanimity, and humor, even while enduring searing personal tragedies.

For his part, Ruckelshaus started out as a lawyer from Indiana, where he served in the state legislature. While he was still in his 30s, he was appointed by Nixon to serve as Assistant Attorney General for the Department of Justice Civil Division, and then as the first administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. In the latter position, Ruckelshaus staffed the new agency, developed its mission and priorities, and built its organizational structure. During this consequential time, he set the standard for how the developed world would manage environmental challenges in the decades to come.

Among other accomplishments, Ruckelshaus oversaw the implementation of the 1970 Clean Air Act, perhaps the most comprehensive air-quality law in the world at the time, and single-handedly overturned a judge’s decision that would have allowed the continued use of the carcinogenic pesticide DDT. That move alone – a worldwide ban soon followed – most likely saved tens of thousands of lives.

William (Bill) Ruckelshaus (pictured left), July 01, 1983

MORAL TRIALS

After the EPA, Ruckelshaus was tested like never before. In recognition of his effectiveness and reputation for integrity, he was temporarily put in charge of the FBI, and then named Deputy Attorney General. When the Watergate scandal began to escalate, Nixon ordered his attorney general, Elliot Richardson, to fire Archibald Cox, the special counsel who had been appointed to investigate the break-in at the Democratic National Committee.

Richardson and Ruckelshaus, anticipating that order, had discussed how to respond. Having been in office for only a few months, Richardson had not yet gotten his head around needing to leave his new job. But Ruckelshaus drew a line in the sand, making clear that he would not carry out the order. That helped prompt Richardson to do the same. Both men resigned, and the firing of Cox fell to Solicitor General Robert Bork, who followed through with the order. Within a year, the “Saturday Night Massacre” would form the basis for obstruction-of-justice charges and Nixon’s eventual resignation in the face of inevitable impeachment and removal from office.

Years later, when Richardson died, he was eulogized as the “Watergate martyr.” And yet it was Ruckelshaus who never hesitated when confronted with the moral test of a lifetime. It was he who set the example and helped to preserve the rule of law from unprecedented attacks.

When Ruckelshaus returned to the EPA in 1983 at the request of then-President Ronald Reagan, he inherited an agency that was in crisis over the mishandling of the Superfund program, created to clean up hazardous-waste sites. As one of the country’s most trusted public servants, he was able to recruit officials with skill and integrity. Within two years, he and his staff had fixed the agency’s reputational problems.

Ruckelshaus then went on to serve as CEO of Browning Ferris Industries. When the company suffered a downturn, he refused to accept the bulk of his compensation, and never told anyone about it. He didn’t want credit; he just thought it was the right thing to do. In the ensuing years, he continued to pursue public service, co-chairing the Joint Ocean Commission Initiative and serving on numerous other United Nations and government commissions.

PLANES, TRAINS, AND AUTOMOBILES

Around the same time that Ruckelshaus arrived in Washington, DC, Grinstein was launching a consumer-protection crusade. A young lawyer from Seattle, Grinstein was chief of staff and chief counsel to US Senator Warren Magnuson of Washington, then the chair of the powerful Senate Commerce Committee. Under Magnuson’s savvy stewardship, Grinstein led a team that drafted landmark legislation to require fair labeling and safe packaging, prohibit deceptive advertising, and enable the purchase of generic drugs. He also played a central role in introducing cigarette warning labels, key automobile safety requirements, product warranties, and regulations barring the use of flammable materials in children’s clothes. These laws fundamentally reshaped the relationship between consumers and the private sector, and saved countless lives.

From Capitol Hill, Grinstein entered private law practice before being appointed CEO of a struggling transport company, Western Airlines. At a time of deregulation and industry consolidation, Grinstein merged Western into Delta to ensure its ongoing viability, and then moved on to serve as CEO of Burlington Northern Railroad. While in that role, he took the business public as an independent entity and added the Santa Fe Railway, creating what was then the world’s largest railroad company and a key engine of global economic growth.

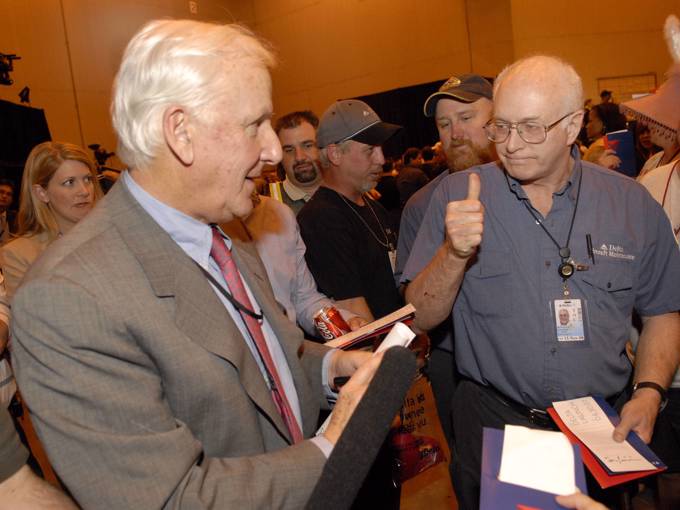

Gerald “Jerry” Grinstein, April 30, 2007

In his 70s, Grinstein finally settled into quasi-retirement, serving on numerous corporate and nonprofit boards, before being asked to serve as CEO of Delta Air Lines just when it was facing bankruptcy. He joined a company whose rank and file had lost trust in the leadership. In a show of good faith, he cut his compensation well below that of his lieutenants, to around the level of senior pilots. He then turned down a multimillion-dollar bonus, directing that the money instead be used to create a scholarship fund for the children of Delta employees.

Like Chuck Krulak, Grinstein walked the walk: he began showing up, unannounced, at the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Airport (a Delta hub), where he would volunteer with the midnight cleaning crews and get on his hands and knees, cleaning toilets. Within months, Delta employees knew that their leader was in the trenches with them.

As Grinstein maneuvered to take Delta out of bankruptcy, he fended off an unwanted merger bid by US Airways by deftly working a critical US Senate hearing in Delta’s favor. With the knowledge and skills that had made him a lion of that legislative body decades earlier, Grinstein won the backing of Congress as well as Delta’s creditors. The airline would go on to become one of the industry’s strongest companies.

LIGHTING THE WAY

By any standard, the Krulaks, Ruckelshaus, and Grinstein are paragons of public service, moral leadership, and career success. But the most enduring lesson these men can teach us has nothing to do with outward achievement. After all, no one makes it through life unscathed. Between all of the public successes, these men also faced huge setbacks and personal tragedies, including losing a wife to complications in childbirth and a number of children to accidents.

Everyone processes loss differently. Some never recover, but some find ways to keep going – to stay positive. To spend time with these men is to be subsumed in their jokes and to witness their pride in their rebuilt families. One can only marvel at how many public-service projects still command their attention (and at their total devotion to mediocre local sports teams, to say nothing of Ruckelhaus’s propensity for brightly colored pants). If you ask them their secret to overcoming trauma, they will demur. But their actions speak for themselves: keep moving forward and pursuing worthwhile activities; look to the future; help others; and seize every opportunity to laugh with friends.

In 2015, Grinstein reached out to President Barack Obama. The White House was drawing up a list of candidates for the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and he quietly put in a good word for Ruckelshaus, his friend of 50 years. Obama already admired Grinstein, so it didn’t take too much prodding to persuade him to recognize one of America’s foremost living patriots. A few months later, Obama bestowed Ruckelshaus with the country’s highest civilian award, analogous to the Medal of Honor. It was the honor of his lifetime.

Ruckelshaus didn’t know that Grinstein had played a part in that award, nor did he ever speak publicly about how he helped Richardson find the right response to Nixon’s unethical order. Acts of true selflessness and moral leadership have nothing to do with recognition. They are about character. Three years into a presidency defined by hubris and a lack of moral character, they illuminate a path that has never been more important for Americans – whatever their political beliefs – to strive to follow.